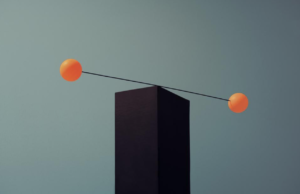

Weighing Your Analytical And Emotional Intelligence Balance

Have you had the experience of working with or for an individual who only seemed capable of operating in an analytical mode? They want facts and figures, details and solutions. It may never even occur to that person to ask you how you are.

On the other hand, you’ve probably also had the experience of working with a colleague who values creativity, compassion and group unity. It would never occur to this person to not ask you how you are.

There isn’t a right or a wrong here, just a dominant use of the individual’s analytical intelligence or emotional intelligence. The point is for leaders to be able to recognize the difference and for them to cycle from one approach to the other depending on the needs of the moment. If your dominant mode is being used too often, you’re missing out on the benefits of your minor mode.

Emotional intelligence can assist you in employee coaching sessions and negotiation and help you be open to new ideas. Developing a social connection with your team or coworkers can build trust and camaraderie. It’s a great way to improve morale. Paying attention to your feelings about your career path, your current projects and your motivation can pay impressive dividends. If you make the time to be self-aware you’ll be able to create the space to consider new ideas or new ways of doing things.

In his book Emotional Intelligence at Work, Hendrie Weisinger, Ph.D. explains, “You can maximize the effectiveness of your emotional intelligence by developing good communication skills, interpersonal expertise, and mentoring abilities. Self-awareness is the core of each of these skills because emotional intelligence can only begin when affective information enters the perceptual system.”

Your emotional intelligence can be utilized for very positive results. In his article, “When It Comes To Success In Business, EQ Eats IQ For Breakfast,”Chris Myers offers, “People buy emotions, not products. Teams rally around missions, not directives. Entrepreneurs take on incredible challenges because of passion, not logic.”

Analytical intelligence is a key skill when you need to solve a problem or make a decision. Seeking out concrete facts and being detail-oriented is essential to completing complex tasks. It’s also an invaluable skill for planning projects, timelines and assigning resources.

Most people are capable of flowing back and forth, even if it isn’t natural or comfortable. Some people do tenaciously cling to one mode, refusing to be flexible — usually to the detriment of their long-term career possibilities.

I once worked with an associate who was firmly entrenched in the analytical approach. He was a wonderful resource when data analysis was needed or facts needed checking. He left nothing to chance and was very thorough. I never had to question the quality of his work.

All of these traits served him well, but he was incapable of toggling over to emotional intelligence mode and consequently was constantly being reprimanded for treating customers badly, and he had a stubborn inability to cooperate with his teammates. He wasted so much of his manager’s time by having to be chastised on a regular basis. In the entire time I worked with him, he never advanced in the company.

Obviously, the inverse situation of solely depending on emotional intelligence is equally detrimental. At another company, I worked in the same project team as a coworker who took everything personally and would sulk because of any real or perceived criticism. She also craved personal interaction even during times she was supposed to be working on her assignment. She disrupted the team so frequently that the project manager had to terminate her. It was unfortunate because she was quite good at what she did.

There is scientific proof that people’s brains process emotional and analytical information differently. Research by Anthony Jack and his colleagues has shown that the analytical network of our brains and the empathetic network work mostly independently. When we’re in one mode, the other mode is suppressed, so the ability to cycle between the two is optimal.

In the book Helping People Change: Coaching with Compassion for Lifelong Learning and Growth by Richard Boyatzis, Melvin Smith and Ellen Van Oosten, the study is discussed in detail. They reflect on how subjects who received a coaching session involving analytic questions and were reminded of it while having their brains scanned had different sections of their brains show activity than the subjects who were given questions based on emotion during their coaching session.

The main takeaway here is to understand when one process is more useful for the situation than the other at any given time. Successful leaders are those who can switch back and forth quickly and with little effort. If that isn’t your strong suit, set aside some time every day to work on it. Like anything else, practice makes perfect.